Almost Git-Flow

I recently shared how I use Git to automatically track my versions. There’s quite a bit more to my git workflow than just tagging versions, though, so I’d like to dive into my git usage just a little more.

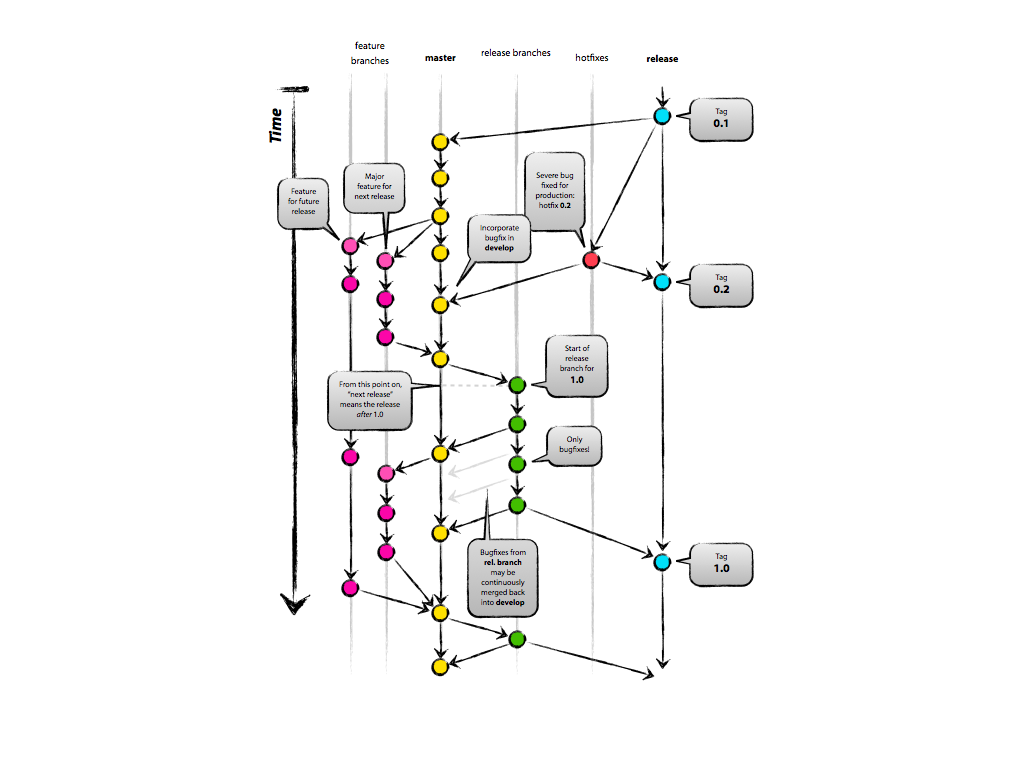

One of my clients introduced me to a very popular, and useful, git branching strategy commonly called Git-Flow based on Vincent Driessen’s branching model. I highly recommend reading his article, it’s quite good and describes a very useful branching model.

My initial reactions were that this was quite a complex model, but as I’ve used it more and more, it’s quite good. I never realized how useful it is to have each release exist on it’s own branch when that last user of version 0.0.1 reports an issue that I never noticed.

Git-Flow⌗

The basic idea is to have a main development branch, often called develop, which is where all feature branches start and end. Those feature branches are where the actual development of each feature happens. When develop is close to being a release, a release branch is created, and only bug fixes go there. Once that release branch is approved, it is merged into master, tagged with the version, and all bug fixes are merged back into develop.

This is a great model, and I enjoy using it, but there are a few drawbacks. The first is in the naming convention.

Master is Develop⌗

First of all, I generally use Github to manage my git repositories. When I’m not using that I use Bit Bucket. Both of these are excellent git management systems, but they all assume that master is the main branch.

I often times use the Github or Bit Bucket web interface to either reference code, or help others with a second set of eyes, and having to always switch to the web interface to develop to see the latest code is a hassle. I can certainly understand why you would want people looking at your main branch, or checking it out for the first time, to see a stable build, but that isn’t how I work. My code repo is for developers, not user, so they don’t need stable code, they need the latest code.

In my flow, I use the same idea, but I call Driessen’s develop branch master. This allows me to regularly work from the master branch. I still need a release branch though, but I simply call that release.

While I’m preparing for a release, I still use release-* branches, but those are quite temporary, since my actual release will get a tag, so the branch doesn’t still need to exist.

Tagging Releases⌗

Now let’s talk about tagging. As I’ve mentioned before, I like to have my version strings pulled automatically from Git. There are a few advantages to this, not the least of which is that it forces me to mark my releases in Git.

This also means that I can’t only tag official releases. You know, like 1.0. As a freelancer, and also for my personal projects, I like to make quite a few alpha and beta builds before a final release. Each of these will get a tag, in addition to the final release tags, so that I can easily identify them all.

Basic Workflow⌗

To give you a high level idea of my basic workflow, which honestly doesn’t diverge much from Driessen’s, here is a glimpse into my day.

-

I’m starting a new feature today, so I create a branch off of master.

$ git checkout -b feature-awesomeness -

Now that this feature is ready, I push it to Github and submit a pull request (for team projects) or I merge it in myself.

$ git checkout master $ git merge feature-awesomeness --no-ff -

Master is looking really good and I think I’m ready to release it, so I create a release branch and choose a version number. Since I want a version string automatically generated, I tag this as my first alpha release.

$ git checkout -b release-1.4 master $ git tag -a 1.4a1 -

I’ve put out my alpha release, but testers reported bugs. I fix them all on the release branch so I make the fixes, tagging each successive alpha/beta/pre-release build.

$ git checkout release-1.4 // Make my changes $ git commit -a -m 'Fixed that minor issue' $ git tag -a 1.4a2 -

All of my testing is great, I’m ready for my actual release. Now I merge the release-* branch into release and tag it, but I also merge it into master so my bug fixes come with.

$ git checkout release $ git merge release-1.4 --no-ff $ git tag -a 1.4 $ git checkout master $ git merge release-1.4 -

Now that I’m done with the release-1.4 branch, it’s toast. But don’t worry, if we ever need to reference it we have tags for that.

$ git branch -d release-1.4 -

Shit! A user has reported a bug in release 1.4, I need to create a hotfix branch from that tag and start my fixes. Tags are created here, as well, for every testing release.

$ git checkout 1.4 $ git checkout -b hotfix-1.4.1 $ git tag -a 1.4.1a1 -

My hotfixes are finished, so that gets merged back into both release and master to ensure that it makes it in the next release.

$ git checkout release $ git merge hotfix-1.4.1 --no-ff $ git checkout master $ git merge hotfix-1.4.1 --no-ff -

Now that I’m done with the hotfix, it’s safe for me to delete the branch.

$ git branch -d hotfix-1.4.1

Next Steps⌗

Aside from those minor changes, everything works pretty much the same as Driessen describes. Hotfix branches come off release and get merged back into both master and release. All temporary branches (feature, release-X, hotfix) get deleted upon completion.

This has worked out quite well for me, so far. My next step is to checkout some of the excellent tools others have created, like git-flow cheatsheet, which adds macros to help you manage all of these branches. This allows custom naming conventions per repo, so this could be a very good option.

Does anyone have any other branching models that they find particularly helpful? Do you find git-flow extremely useful with or without modification? Share your thoughts in the comments.